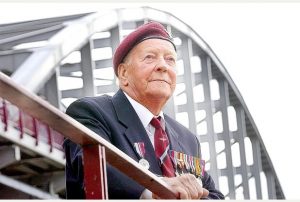

‘The bullets tore holes in my parachute… It was complete chaos. We tried to get forward; I was firing the Bren gun. A couple of men dropped to this side of me, a couple dropped that side. One got split down the middle by machine gun fire.’

‘The bullets tore holes in my parachute… It was complete chaos. We tried to get forward; I was firing the Bren gun. A couple of men dropped to this side of me, a couple dropped that side. One got split down the middle by machine gun fire.’

This is how ‘Jonny’ Stillwell described his descent by parachute into Nazi occupied Holland in 1944. The drop zone, Ginkel Heath, about 8 miles from Arnhem Bridge, was a scene from hell, the heathland was on fire, the men from the sky were being shot at with everything the Germans and Dutch Nazis had, anti-aircraft flak and machine guns. John was a mere twenty-two years old but already a battle-hardened veteran of North Africa and Italy, now trained and honed as an elite soldier, one of a real band of brothers.

John went on to say when describing the drop, ‘that was the first time in my life I knew there was somebody up there looking after me. I believed; I believed’

Leicestershire boy, John was a private in the 10th Battalion, the Parachute Regiment. There were around 650 men in the Battalion. He had been with the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Sussex, in North Africa at the battle of El Alamein and took part in the seaborne invasion of Sicily. He was there when far seeing officers from the Royal Sussex, which was decimated in N. Africa, decided to convert the battalion to one of the new-fangled parachute regiments. He was there on a snowy day in December 1943, arriving in Somerby, his new home. During the long hot summer that followed, John drank and sang in the community hall and pubs in and around the village.

He dropped from the sky onto Ginkel Heath and was captured close to a previously unknown railway crossing in the tiny Dutch village of Wolfheze near to Arnhem.

The day after John descended into the carnage of the drop zone and during which the Battalion had fought a ferocious five-hour battle around a pumping station on the road to Arnhem, he found himself in a small party under the command of Captain Lionel Queripel. They were ordered to hold a tunnel leading to a small finger of woodland to the north east of the vital railway crossing at Wolfheze. This company of men, including John, held the position throughout the night and into the next day with small arms and grenades against heavy mortar and Spandau machine gun fire. As the enemy pressure increased, Captain Queripel, by now wounded in the face and both arms, ordered his men to withdraw and despite the loud protests he remained behind alone to cover their withdrawal. Queripel later died of his wounds and was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross. John told that Queripel was a much loved and respected officer and there is no question that he earned that highest award for bravery but John also said that every man involved in that stand deserved a VC.

In 1945 when these men returned, post-traumatic stress had not yet been invented! There was no counselling, no help; they merely got on with normal life.

It is no wonder that Field Marshall Montgomery after the battle said about John and his comrades; ‘there can be few episodes more glorious than the epic of Arnhem, and the those that follow after will find it hard to live up to the standards that you have set. In years to come it will be a great thing for a man to be able to say: ‘I fought at Arnhem. You are MEN APART, EVERY MAN AN EMPEROR’.

Arnhem was a glorious failure; however, the men who stood firm on the northern banks of the Rhine with only light weapons against the might of armoured German forces for nine days has gone down as legend. John Stillwell was one of these men.